|

The history of Greece from 0 AD to 2023 is a vast and complex journey that spans over two millennia. Here, I will provide a condensed overview of some key events and periods that have shaped Greece's history during this time:

0 Comments

Brazil has a fascinating journey that encompasses indigenous cultures, colonial exploitation, the slave trade, and the eventual struggle for independence. From its discovery by the Portuguese in the 16th century to its transformation into a modern, diverse nation, Brazil's history has been shaped by a multitude of influences.

Japan has a long and fascinating journey that stretches over thousands of years. Here is an overview of some key periods and events that have shaped Japan's history:

The history of Germany is a fascinating and complex journey that spans thousands of years, characterized by significant cultural, political, and territorial changes. Here is a brief overview of key periods and events in the history of Germany:

The history of Spain is a rich and complex tapestry that spans thousands of years. From prehistoric times to the present day, the Iberian Peninsula has been a melting pot of cultures, civilizations, and empires. This historical account provides an overview of some of the key periods and events that have shaped the nation of Spain.

The history of France is a rich and diverse tapestry that spans over thousands of years. From ancient Gaul to the modern-day French Republic, the country has experienced significant political, social, and cultural transformations. Here is a brief overview of key periods and events in the history of France:

THe KingdomThe United Kingdom is an unitary state made of multiple countries inside The British Isles which are England, Scotland, Wales and some parts of Ireland. stats of The United KingdomFounded in: 1922 Gross Domestic Product: 2.708 Trillion (2020) Population: 67.22 Million (2020) Capital: London Type of Government: Constitutional Monarchy, Unitary State, Parliamentary System Type of Economy: Capitalist Current Leader: Boris Johnson The United Kingdom

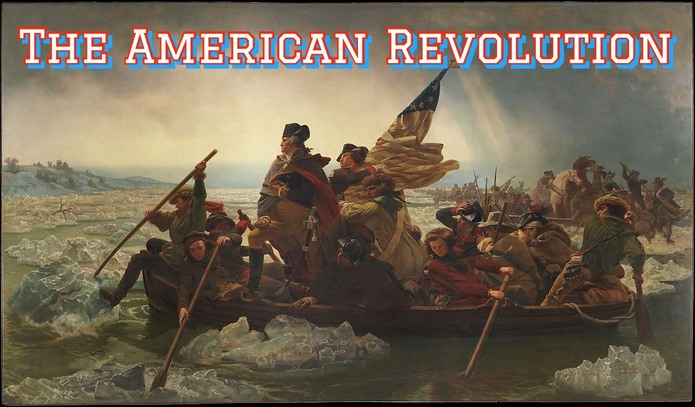

The United States of AmericaThe United States of America is a Federal Republic Liberal Democracy that is located in The Americas. The United States of America is the richest country in The World and is The Super Power of The World as of Today. The United States of America is a multicultural kaleidoscope with many different cultures and subcultures mixed into one country due to its policy of freedom of speech, no establishment of a state religion, openness to immigration, size and no official language. The United States of America is the World hegemony as of Today. The United States has fifty states which are : Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virgina, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Vermont, Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Louisiana, Indiana, Mississippi, Illinois, Alabama, Maine, Missouri, Arkansas, Michigan, Florida, Texas, Iowa, Wisconsin, California, Minnesota, Oregon, Kansas, West Virginia, Nevada, Nebraska, Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, Alaska, Hawaii. The Start of America The United States of America's and The America's in general beginning can be many different events depending on who you ask. Some say it begins way before colonization, when Natives came via land bridge or other speculated way to Turtle Island to mark a new home. Some say it was 1619, when slaves from West Africa were brought to The Americas to serve under the most brutal form of slavery ever practiced by man. Alas, for tradition's sake, we shall start the journey in 1492 with the arrival of Italian Explorer Christopher Columbus in what is Today known as, The Bahamas. Though further south than what would be known as The United States of America, this moment of arrival for The Italian Eplorer would change the course of history for The World, forever! Born in 1451 in Genoa, Italy, Columbus was an explorer appointed by Queen Isabella The First of Castile to travel to The East Indies going West sailing on La Santa Maria in 1492. When Columbus arrived to Turtle Island, he believed that he had landed in South Asia, so when he met The Natives, he referred to them mistakenly as Indians, a term still used today by some people. What was once, just a spirit of exploration, became a yearning for resource extraction. Turtle Island was prime for extraction with its many untouched, untapped resources that could make any King or Queen's wildest dreams of riches come true. Thus began, The Colonial period.  The colonial period was a time of exploration, wonder, land grabbing and exploitation. The New World would be explored and mapped out by many explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci, Hernan Cortes, Henry The Navigator and Marco Polo. In this period of time many new territories were established by European Colonist with land taken from The Native population. A few of these colonies were established by countries like England, Spain, France, The Netherlands and Portugal. For the sake of keeping things focused on The United States of America, let's closer inspect the English colonies. 13 ColoniesThe 13 colonies were New York, Maryland, Virginia, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and New Jersey. The American Revolution The American Revolution, also known as the War of Independence, was a pivotal event that led to the birth of the United States of America as an independent nation. Here's an overview of its history: Background: In the 18th century, the thirteen British colonies in North America were flourishing but were subject to British rule. The British government imposed various taxes and regulations on the colonies, including the Sugar Act, Stamp Act, and Townshend Acts, which sparked resentment and opposition among the colonists who believed they were being taxed without representation. Boston Massacre and Boston Tea Party: Tensions escalated, and in 1770, a confrontation between British soldiers and colonists in Boston resulted in the "Boston Massacre," leading to several deaths. In 1773, the "Boston Tea Party" saw colonists, disguised as Native Americans, dump British tea into Boston Harbor to protest the Tea Act. Intolerable Acts: In response to the Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, in 1774, which further restricted the rights of the colonists and imposed harsh punishments. First Continental Congress: In 1774, representatives from twelve colonies convened in Philadelphia for the First Continental Congress to discuss grievances and coordinate a united response to British policies. Battles of Lexington and Concord: In April 1775, British troops were sent to seize colonial military supplies in Concord. The "Shot Heard 'Round the World" was fired in Lexington, and armed conflict erupted between colonial militias and British forces. Second Continental Congress: The Second Continental Congress met in May 1775, and soon appointed George Washington as the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, tasked with leading the colonial forces. Declaration of Independence: In June 1776, the Second Continental Congress appointed a committee, including Thomas Jefferson, to draft a declaration justifying the colonies' independence. On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress approved the final version of the Declaration of Independence, severing ties with Britain and proclaiming the colonies as the United States of America. The War: The Revolutionary War continued from 1775 to 1783, with significant battles such as the Battle of Saratoga (1777) and the Battle of Yorktown (1781). The American forces received aid from France, which played a crucial role in their eventual victory. Treaty of Paris: In 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed, officially ending the war. Britain recognized the independence of the United States and agreed to the boundaries of the new nation, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River. Constitutional Convention: In 1787, a Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia to draft the United States Constitution, which laid the foundation for the country's governance and federal system. Ratification and Inauguration: The Constitution was ratified in 1788, and George Washington became the first President of the United States in 1789, officially establishing the new nation. The American Revolution not only secured American independence but also inspired other movements for self-determination and democratic governance around the world. It remains a significant event in world history and a defining moment in the creation of the United States. The War of 1812The War of 1812 was a conflict fought between the United States and Great Britain, along with its Canadian and Native American allies, from June 18, 1812, to February 17, 1815. It was a significant event in American history, shaping the young nation's identity and relationship with its neighbors. Background: Tensions between the United States and Great Britain had been simmering for years leading up to the war. There were several key issues that contributed to the hostilities:

Major Events of the War of 1812:

The Civil WarThe American Civil War, also known as the Civil War or the War Between the States, was a devastating conflict that occurred in the United States from April 12, 1861, to April 9, 1865. It was fought between the Northern states, known as the Union, and the Southern states, known as the Confederacy. Causes of the Civil War: The Civil War had deep-rooted causes that had been building for decades before the first shots were fired. The primary issues that led to the conflict were:

South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union on December 20, 1860, and was soon followed by six other Southern states: Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. These states formed the Confederate States of America with Jefferson Davis as their president. The War:

Reconstruction, the period following the war, aimed to rebuild the South and reintegrate the Confederate states back into the Union. However, Reconstruction also faced challenges, including resistance from Southern whites and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, which sought to undermine the rights and freedoms of newly freed African Americans. The Civil War's legacy continues to shape American society and politics, and it remains a pivotal event in the nation's history, demonstrating the high cost of resolving fundamental differences through armed conflict. The American DreamThe American Dream is a concept that embodies the belief that in the United States, regardless of one's background or social status, everyone has the opportunity to achieve success, prosperity, and upward social mobility through hard work, determination, and individual merit. It is often associated with the pursuit of a better life, financial stability, homeownership, education, and overall personal fulfillment. The phrase "The American Dream" first gained widespread popularity during the early 20th century, particularly in the aftermath of the Great Depression. It was often linked to the idea that the United States was a land of opportunity, offering a fresh start and the chance for people to improve their lives and escape poverty or oppressive conditions. The American Dream has been an essential part of the national identity and has inspired countless immigrants and citizens to strive for a brighter future. However, over the years, there has been ongoing debate about the feasibility and accessibility of this dream for all individuals, as economic disparities, systemic inequalities, and other challenges have affected opportunities and social mobility. The World WarWorld War I, also known as the First World War or the Great War, was a global conflict that lasted from July 28, 1914, to November 11, 1918. It involved many of the world's major powers, divided into two opposing alliances: the Allies and the Central Powers. Here's an overview of the key events and developments during World War I:

The Roaring 20'sThe Roaring Twenties, also known as the Jazz Age, was a remarkable period in American history that spanned from the end of World War I in 1918 until the Great Depression in 1929. It was characterized by significant economic growth, cultural shifts, and widespread social changes. Here's an overview of some key aspects of this vibrant and transformative decade:

The Great DepressionThe Great Depression was one of the most severe economic crises in modern history, lasting from 1929 to the early 1940s. It had a profound and lasting impact on the United States and the rest of the world. Here's an overview of the key events and factors that contributed to the Great Depression in America:

World War IIWorld War II was a global military conflict that took place from 1939 to 1945. It involved many of the world's great powers and resulted in significant changes to the political and social landscape of the 20th century. Here is a brief overview of the history of World War II:

The 50'sThe 1950s in America was a decade marked by significant social, political, and cultural changes. After the end of World War II, the United States experienced a period of economic prosperity and rapid technological advancements, which contributed to the growth of a consumer-oriented society. Here's an overview of the history of the 1950s in America:

THe 60'sThe 1960s in America was a tumultuous and transformative decade that witnessed significant social, political, and cultural changes. It was a period of intense activism, protests, and movements that challenged the status quo and shaped the future of the nation. Here's an overview of the history of the 1960s in America:

The 70'sThe 1970s in America was a decade of contrasts, marked by both progress and challenges. It was a period of continued social change, economic shifts, political upheavals, and cultural shifts. Here's an overview of the history of the 1970s in America:

The 80'sThe 1980s in America was a decade of economic prosperity, political shifts, technological advancements, and cultural changes. It was a time of contrasts, with both optimism and challenges. Here's an overview of the history of the 1980s in America:

The 90'sThe 1990s in America was a decade of significant cultural, technological, and political shifts. It was marked by both prosperity and challenges, shaping the modern era in many ways. Here's an overview of the history of the 1990s in America:

The 2000'sThe 2000s in America was a decade marked by significant events, ranging from political shifts and technological advancements to moments of tragedy and triumph. Here's an overview of the history of the 2000s in America:

America Today

The historical odyssey of England unfolds as a complex tapestry interwoven with myriad strands, tracing its genesis to prehistoric epochs and the Roman incursion of 43 AD. In its nascent stages, England bore witness to the amalgamation of disparate tribal entities, establishing a foundation marked by diverse cultural amalgamations. The post-Roman era, commencing in the 5th century, witnessed the ascendancy of Anglo-Saxon dominion, characterized by the proliferation of distinct kingdoms and the assimilation of Germanic influences.

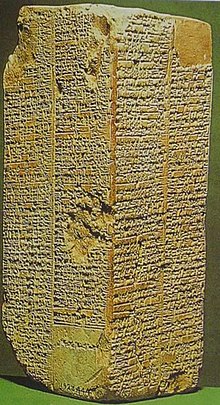

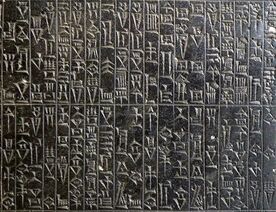

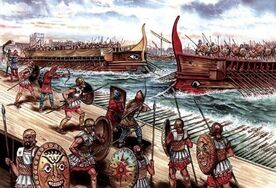

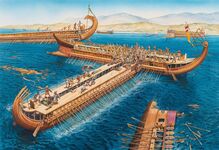

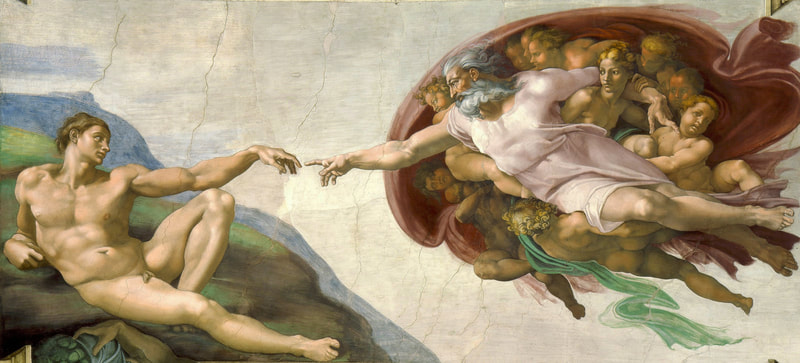

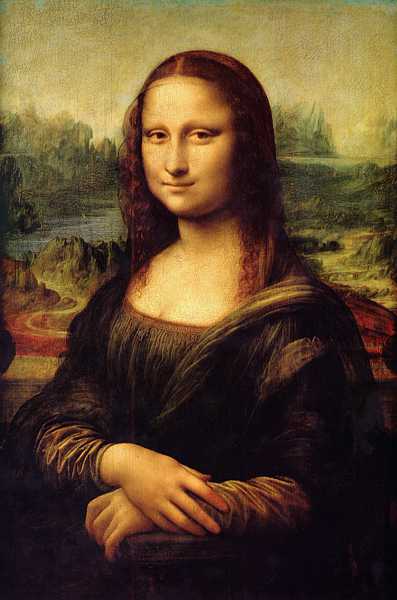

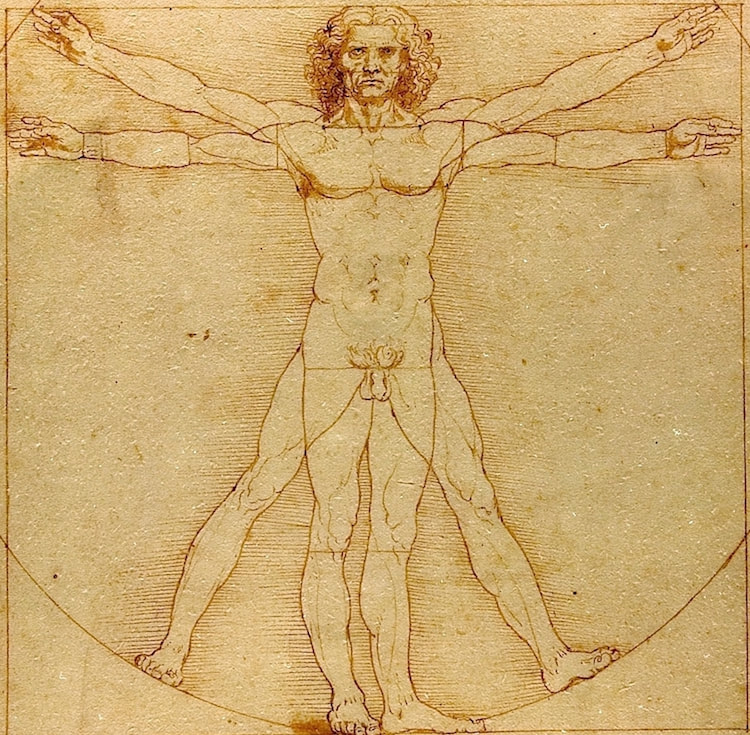

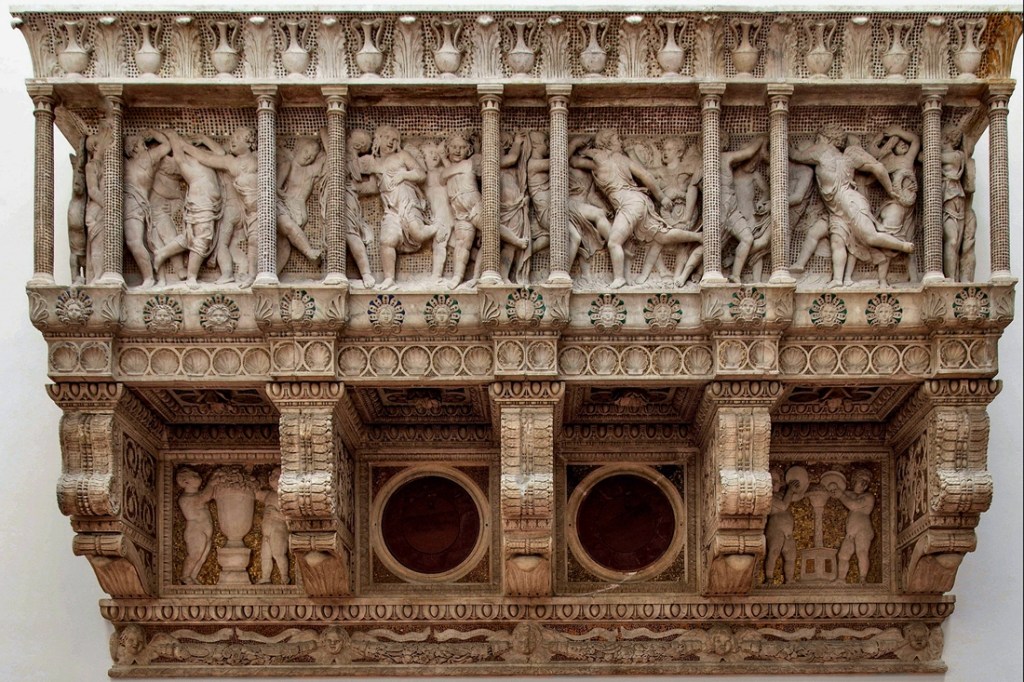

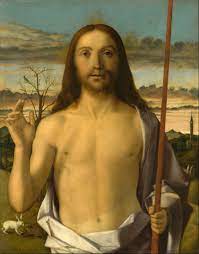

A transformative watershed occurred with the Norman Conquest of 1066, instigating a paradigm shift through the introduction of feudalistic structures and a profound reconfiguration of the socio-political milieu. The ensuing medieval epoch witnessed the consolidation of monarchical authority, epitomized by the reign of the Plantagenet dynasty, alongside seminal events such as the Magna Carta in 1215, which laid the groundwork for constitutional precepts. The 15th-century Wars of the Roses ushered in a tumultuous era of dynastic conflict, ultimately culminating in the ascendancy of the Tudors and the advent of the Renaissance. This epoch, characterized by the formidable reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, bore witness to England's burgeoning influence on the global stage. The Stuart period of the 17th century engendered profound political upheaval, exemplified by the English Civil War and the subsequent establishment of a brief republic under the auspices of Oliver Cromwell. The restoration of the monarchy in 1660 marked a return to equilibrium, fostering the intellectual and cultural efflorescence of the Enlightenment. The 18th century witnessed the zenith of England's imperial prowess, underscored by expansive colonial endeavors, burgeoning trade, and the inexorable march of industrialization. The Victorian era, spanning much of the 19th century, encapsulated the apogee of imperial power, accompanied by seismic social transformations and the initiation of parliamentary reforms. The 20th century unfolded as a narrative punctuated by the crucible of global conflicts, economic vicissitudes, and the ebb of colonial hegemony. England's pivotal roles in both World War I and II, coupled with post-war reconstruction initiatives, solidified its status as a prominent global actor. The latter half of the century witnessed the waning of imperial dominion and the concurrent emergence of a multicultural societal fabric. In the contemporary milieu, England grapples with the intricate dynamics of a post-colonial and post-industrial epoch, navigating complex challenges such as Brexit and recalibrating its global role. The historical odyssey of England stands as a testament to the indomitable spirit of its populace and the intricate interplay of forces that have indelibly shaped its destiny. The Start of Italy Italy is a nation located in Southern Europe on The Mediterranean Sea bordering France, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia and The Holy See. The Capital of Italy is Rome and The Population of Italy is 60,553,000 circa 2020. The Native Language of Italy is Italian which comes from Latin, the original native language of Italy. The most practiced religion in Italy is Roman Catholicism with 83 percent of Italians claiming to be Roman Catholic in 2005; 14 percent of Italians are Atheist/non-religious, 2 percent practice Islam and 1 percent declare other in the same year reported. The currency of Italy is The Euro. Italy has a Gross Domestic Product of 1.88 Trillion USD circa 2020. Italy's government is a Unitary State Constitution Parliamentary Republic, kind of a return to Roman Tradition.  The Start of Italy and its place in Today's World would have to start in a time before its creation. That would Rome before it was The Capital of Italy, was The Superpower of The World. Controlling about all of the Mediterranean and beyond stretching from The British Isles to Egypt and from Spain all the way to Anatolia. Rome is located in The Italian Peninsula and its expanded started with the conquering of this Peninsula. This Peninsula in the Mediterranean Sea is what is Today known as Italy. The Fall of Rome and The rebirth of Roman excellence IN 476 A.D., The Roman Empire fell due to political instability and invasion of Germanic tribes known to The Romans as Barbarians. This collapse started what would be know as The Dark Ages, The Middle Ages or The Medieval era. This was a time of Medieval Kings or other such royalty, rallying and warring over the land that was once part of The Roman Empire and the surrounding areas of modern-day Europe. Monarchy and Religious extremism ruled Medieval Europe and the light of knowledge would not belong to the people till a thousand years later when The Renaissance would begin in the same place where that light ended, Italy. The Kingdom of Italy The Kingdom of Italy, also known as The Ostrogothic Kingdom was founded in 493 A.D. by The Germanic Ostrogoths with The First King of Italy, Flavius Odoacer. Flavius Odoacer was born in Pannonia, The Roman Empire (modern day Austria), in 431 A.D. Flavius became The First King of Italy in 476 A.D. when he toppled The Emperor of The Roman Empire Romulus Augustus and dissolved The Western Roman Empire, establishing The Kingdom of Italy. King Odoacer would be a client of The Eastern Roman Emperor Zeno but still be The Power of The Kingdom of Italy. Rex Odoacer would reign as The Rex of Italy until 493 A.D. when he when Theodoric had him killed after many campaigns of battle. Theodoric was promised the crown of the Italian peninsula by Emperor Zeno and in 493, The King of Ostrogoths would became The Second King of Italy, Theodoric The Great. The Capital of The Kingdom of Italy was Ravenna till 540 A.D.  King Teja, also known as Teia, Thila, Theia, Thela or Teias, was The Last King of Italy. King Teja would reign as King of Italy till 552 AD after being killed in The Battle of Mons Lactarius; where he would lead a fleet to kill all Roman Senators as an act of revenge for a defeat earlier at Battle of Taginee where King Totila, the king of Italy before him was killed. He also ordered the slaughter of about 300 Roman Kids that were hostages of the previous King. After creating a deal with The Franks in Pavia, he fled to Southern Italy with the support of several military leaders who were under the previous King of Italy, Totila. When he and his army made it to Mount Vesuvius, King Teja was killed in battle at what is known as The Cataclysmic showdown where The Ostrogoths were defeated by The Romans. After the fall of The Final King of Italy, The Ostrogoth people assimilated into boarder Italian Culture and faded into insignificance. The End of The Kingdom of Italy. Medieval Italy IN 535 AD Roman General Justinian declares that all of Italy is a part of The Eastern Roman Empire. This start a war known as The Gothic War, which is fought between The Roman Empire and The Kingdom of Italy until 554 AD where King Teja is killed. This would remain until 568 AD, when the Lombards would invade and take over much of Italy. The Romans would ruled The Ravenna province of Italy while The Lombards who control the Pavia province. The Lombards were a northwestern Germany Germanic tribe. The Lombard's were able to win Italy from The Romans due to it being left defenseless by The Romans after their win against The Kingdom of Italy. In fact, in 569 AD, they crossed over The Julian Alps into northern Italy unopposed by the inattentive Romans. They would capture Pavia in 572 AD. The Lombard Kingdom of Italy would reign until 774 AD. when The Pope, Pope Adrian The First, asked for help from The Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne, just a Frankish King at the time, to take down The Lombards invasion of The Papal States. Charlemagne's army would defeat The Lombard's in The Pavia siege in 773 that lasted one year, which would end the reign of The Lombard Kingdom of Italy. The Lombard's name would remain in Italy till this day in the region of Lombardy. In 800 AD, Charlemagne would be crowned, King Charlemagne, The First King of The Holy Roman Empire, or The Carolingian Empire. Northern and Central Italy would be in the territory of The Holy Roman Empire. Until the 9th century where the Carolingian Empire would disband, The Holy Roman Empire would continue on however, which will leave behind several Italian States which would rival each other for power and territory. After this point, all of the action occurs in Southern Italy and The Island of Sicily. In the 11th century, both Southern Italy and Sicily would be control and colonized by The Normans, a Nordic/viking peoples from Northern France in a region which is known today as Normandy. This would kick off a power struggle called for by The Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII which would start a 200 year conflict in Italy which would end in a Pope Victory in 1250 AD.  96 years later, in 1346, a catastrophic event would begin which would change The World forever. Coming from East and/Or Central Asia; The Black Death, also known as The Black Plague or The Bubonic Plaque would ravage Europe and North Africa beginning in Italy and Sicily. For 7 years, Italy and all of Europe was ravaged by this apocalyptic disease. Religious Zealots claimed it to be a punishment from god and many would whip themselves to atone for sins committed by people who lived in the most religious time period in history, very logical. In the 7 year span of The Black Death 25 million people met their expiration at the hands of the Bubonic Plaque. Through the implementation of quarantines, the plaques grip on Italy and the rest of Europe would cease to hold. This plaque may have brought death and destruction, but in it's wake, the course of history of Italy and The World, would change forever. The Renaissance Beginning in Florence, Italy around 1300 AD, The Renaissance would be the rebirth (Renaissance means Rebirth in French) of excellence in the arts and sciences for those in the European continent, that was lost when Rome fell almost a millennium earlier. With this new era, The Medieval Times had ended and a new chapter in history would begin, one of many goods and one of many evils. The Renaissance can best be describes as The Rise in European interest in The Classical World's Philosophy, Political Structures, Arts, Ideas, etc. This led to a brand new ideology/philosophy, that was based on Secular Values as opposed to The Scholastic Religious Values on The Medieval Church, known as Humanism. According to the fourth definition presented by The Oxford Dictionary as of 2021, Humanism is "Devotion to those studies which promote human culture; literary culture; esp. the system of the Humanists, the study of the Roman and Greek classics which came into vogue at the Renascence."[sic] and the second definition being "The character or quality of being human; devotion to human interests". This new ideology would put more focus on the human and the material world rather than that of the metaphysical; which would bring about new technologies and better knowledge of The World which would advance humans beyond what those who lived in The Medieval Era would have ever thought possible without Magic. The Renaissance would bring about some of the most famous artist of all time which included Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, Donatello, Raphael and Giovanni Bellini. Michelangelo would create art such as The Creation Adam, The Sistine Chapel ceiling and The Statue of David; Leonardo Da Vinci would create The Mona Lisa, The Last Supper and The Vitruvian Man; Donatello would create art such as Saint Mark, The Feast of Herod and Cantoria; Raphael would create art such as The School of Athens, Transfiguration and The Disputation of The Holy Sacrament; and Giovanni Bellini woudl create art such as The Feast of The Gods, Christ Blessing and Agony in The Garden. Michelangelo Leonardo Da Vinci Donatello Raphael Giovanni Bellini One of the most famous part of The Renaissance in Italy, is the Medici Family. The Medici family would bring about the high point of The Renaissance. The Medici Family would reign over the city of Florence, Italy most of the Renaissance. Their contributions to The Arts and Humanism with the money made from being bankers and wool merchants would help fund the Renaissance to be as impactful as it was. The order to Renaissance given by the rule of The Medici's would start to fall apart in 1495, when The King of France Charles The Seventh, would invade Italy and push the Medici family from Florence. In 1503, The Center of The Renaissance is moved from Florence, Italy to Rome, Italy; Rome is once again, The Center of The World. In 1527, The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V would sack Rome which would lead to Venice, Italy becoming the center of art. In 1527, The Renaissance would end due to primarily The Protestant Reformation causing conflict in Europe which would see funds given to war efforts as opposed to the arts. Spanish ItalyAfter The Sacking of Rome, The Medici Family was expelled from rule in Florence and in 1528 The French General Odet de Foix Lautrec's army would arrive in Rome to establish control of the peninsula. However, The Aristocrat Admiral Andrea Doria would double-cross The French, which he once was under the service of, in service of The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. A Plaque would take The Aloha from Odet de Foix Lautrec which would destroy most of the French Army, forcing The Pope in 1529 to sign The Treaty of Barcelona, giving Spain control over Italy after 40 years of war. In 1530, The Pope would crown Charles V The King of Italy. In exchange for The Medici's being given back control over Florence, The Pope promised to address the protestant reformation and reform for the church. The Spanish would reinstate The Medici family as the rulers of Florence. In 1530, Spain would establish complete control of Italy, besides Venice. Most Italian states would remain Independent however, with the exceptions of Sicily, Naples, Milan and Sardinia. Even with the declared control of Italy by Spain, French and Spanish conflict over the rule of Italy would still persist until April 3rd, 1559; where The Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis would be agreed upon. This agreement would end a 65 year conflict between the two roaring nations over who would control Italy. Hapsburg Spain would now officially dominate Italy for 150 years. Austrian and French ItalyIN 1700, The Last Spanish Hapsburg Charles II, would die. This would begin state relations between Italy, Austria, The Spanish Bourbons and The Independent States. This would lead to Austria to become the main power over Italy. This would persist until 1796, when Napoleon invades Italy and establish the Ligurian Republic in 1797 in Genoa, Italy. In 1805, The Ligurian Republic would be incorporated into The French Empire. Italy seemed to be doomed to be ruled as a French state forever, until 1814, when French control over Italy would be overthrown, and a series events that would lead to The Unification of Italy would begin. The UNIFICATION of ItalyIn 1815, The Congress of Vienna, an International Diplomatic Conference meant to restore European Political Order after the fall of The Napoleonic Empire, would establish the boundaries of The European Nations. Venice, Italy is given to Austria in 1815. Fascist Italy  Fascism was an ideology invented by Benito Mussolini in 1915. This ideology was forwarded by Mussolini to conquer Italy and make Mussolini the dictator of Italy. Mussolini's main goal was to reestablish the fallen Roman Empire to its former glory. He did this with conquest of former Roman Empire land such as Ethiopia. He would later join Adolf Hitler as allies in the axis powers in World War 2. The Italian People would eventually hung Mussolini and join the allied powers to defeat Nazi Germany and win WWII in Europe. Italy TodayToday's Italy Capital is Rome and boosts a population of 59.55 Million (2020). Today, Italy is a Unitary State, Parliamentary Constitutional Republic.Today's Italy economy is a diversified industrial economy. The current Leader of Italy is Prime Minister Mario Draghi (2021). Related ArticlesThe Start of RomeThe Trojan War was a Super Awesome Powerful Legendary War between The Trojans of Troja(Troy) and The Classical World (Greeks). The Classical World Won The War with the Trojan Horse. The Warriors of The Classical World hid inside The Trojan Horse which was a giant wooden horse that acted as a surrendering gift to The Trojans. The Trojans did not think twice about bringing this ‘gift’ into their city walls of Troja. That night, The Trojans threw a Party and become quite intoxicated. When the time was right, The Classical World Warriors came out of The Trojan Horse and laid siege to Troja. The Classical World claimed Victory in The Trojan War. Not all Trojans were slaughtered however and escaped from the ruins of their once great city. The fleeing Trojans (outlined in The Aeneid) would eventually make their way to the land of Latium. This land in Italy would one day be called Rome! Romulus and RemUs The Founding of Rome cannot be told without the Legendary story of how it was founded. The Story of Romulus and Remus. Alba Longa, a kingdom in Italy, had a King. King Numiton is The Grandfather of who would be the founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus. Numiton had a brother named Amuliud. Amuliud was jealous and wanted to take Numiton's place as King of Alba Longa. Amuliud slains Numiton and his son then kidnaps Numiton's daughter Rhea Silvia. In order to stop any legitimate opposition for the throne, Amuliud forces Rhea Silvia to become a vestal virgin & unless you are Holy Mary, thou need to have coutius in order to beget children. However, this would not stop the fate of Amuliud's demise for The Roman god Mars, The Roman god of War, has relations with Rhea Silvia and conceives and gives birth to twin brothers Romulus and Remus. Hearing of this birth, Amuliud sends his servant to cast them into the river and to drown them. His servant however cannot bring himself to commit this infanticide. Instead his servant puts the twin brothers into a basket and send them down the stream. When the carriage finally ceases to stream, the baby brothers land on what would eventually become The City of Rome. Thence a she-wolf discovered them two boys and weens them and takes care of them for a time being; raising them as fellow wolves. Later on a herdsmen named Faustulus and his wife Acca Larentia. Romulus and Remus are thence brought up as shepherds. Romulus and Remus, Naturally, become Adults and come to learn of a corral The Loyalist of Amuliud and The Loyalist of Numiton. During this corral they learn of their true origins and that Numiton was their Father. The most important thing they learn though, is that they were destined to become Kings! With the passion of a lion stalking its prey, Romulus and Remus Join The loyalist of their late father Numiton. They then end up slaughtering and overthrowing Amuliud and avenge their Father. The vengeance was sweet as a cherry pie in mid-spring with a cool breeze flowing through thy hair. With that they establish as new kingdom set where the she-wolf discovered and nursed them as infants. This kingdom will become Rome. There was dispute on who owned what and where the kingdom was to be placed. The two split their kingdoms with Remus's land on Mount Remus and Romulus on Palatine Hill. In the end, they both knew that one would become sole sovereign of The Kingdom. Remus was the first to see birds fly over head which made him to claim control over all the lands. However, Romulus saw twofold the amount of birds(12) that Remus saw, so he claimed to own all the land. Romulus built a wall around his territory to keep out invaders. Remus laughed and mocked this wall saying that it could not keep invaders from crossing into his lands. Remus then proceeded to jump back and forth across the wall, mocking Romulus. In a fit of rage, Romulus slaughtered his brother and become The Sole ruler of The Kingdom of Rome. Romulus, What Hast thou done? Thou hast slain thy brother. Thou hast Cain thy Abel. His blood flows through thy kingdom and his vengeance shalt be dealt to thee. For yay, thy land shalt be great indeed, but with thy brother's slaughter, thou Kingdom wilt never stretch across The World nor will it last forever. For it is doomed to only last a millennium. For thy legacy and Father's Legacy, Mars, shalt be taken and given to a different son of God and God. Rome shalt last, but thine Rome shalt Fall. The First King of Rome Rome would be established on April 21st, 753 B.C. This day would known as Parilia. With the murder of his brother Remus, Romulus would become The First King of Rome, The Rex of Roma. He declared himself The King of Rome after killing his brother Remus. In The Early days of The Roman Kingdom, any man could join the ranks as citizen. Naturally this brought in a significant portion of outlaw men into its citizenry. But as is all to well known, without a future generation to pass the torch down too, the future of the civilization will be non-existent. And of course, it takes two to tango. With a population of just men and no women, reproducing could not occur. To help bring in wives for his men to reproduce with, Romulus Rex tried to negotiate with The Sabine peoples to offers some of their women in order for The Roman Kingdom to survive into future generations. The negotiations fell flat however & The Sabine people refused to give their women to The Romans. Naturally, this would not work for the Romans, so Action must be taken to prevent The Extinction of Roma. During The Festival of Neptune Equester, The Roman Men kidnapped The Sabine Women and fought off The Sabine men's attempt to stop The Roman abduction of their women. This attempt by The Sabine men was unsuccessful however and The Superior Romans took The Sabine Women as Wives. This event was known as The Rape of The Sabine Women. A War broke out against The Romans and The Sabines with other Italian Tribes. The First battle was fought when The Caeninenses invaded Roman territory. Big mistake however, for Romulus and his men slaughtered The Caeninenses King. The Sabines later on would Officially declare War on The Kingdom of Rome. Because of the traitor Tarpeia, The daughter of Spurius Tarpeius, The Sabines and their King Titus Tatius was about to enter The walls of Rome and capturing it. The Sabines were dead set on killing every last Roman with no mercy. Romulus rallied The Romans to counter attack the Sabine advance and pin them at the gate of The Palatium. The Wives of The Romans, The Captured Sabine Women, got in the way and pleaded for their husbands and their former folk to cease the fighting. The Roman Kingdom The Kingdom of Rome lasted from 753 B.C. with The First King of Rome, Romulus to 509 B.C. He reigned till his day of passing in 716 B.C. at the Age of 56. It is legend that he was swept away by a whirlwind from a colossal brutal storm. In this storm he told to have ascended into Heaven to join his Father, The Roman god of War, Mars. Romulus Rex's successor was The Second King of Rome and his Brother-in-Law, Numa Pompilius. Numa Pompilius took the throne in 715 B.C. when he was elected to be Rex by The Curiate Assembly. Rex Numa Pompilius was from The Sabine Region of The Italian Peninsula. Rex Numa Pompilius was accredited to many important things for Roma including The Roman Calendar, The Cult of Jupiter, The Cult of Mars, The Cult of Romulus, The Vestal Virgins and the religious office of Pontifex Maximus. The Roman Calendar was The official calendar used by The Roman Kingdom and later Roman Republic which would later be reformed in The First Century B.C. by Julius Caesar becoming The Julian Calendar which would be later reformed by The Catholic Church into the calendar we use in Today's World known as The Gregorian Calendar. The Roman Calendar was a ten month calendar which included the months: Menis Martius or March (Month of Mars), Menis Aprilis or April (Month of Apru or Aphrodite), Mensis Maius or May (Month of Maia), Mensis Iunius or June (Month of Juno), Mensis Quintilis or July Later on being named after Julius Caesar (Fifth Month), Mensis Sextilis or August later on being named after Augustus Caesar (Sixth Month), Mensis September or September in Today's World (Seventh Month), Mensis October or October in Today's World (Eight Month), Menis November or November in Today's World (Ninth Month) and Mensis December or December in Today's World (Tenth Month). The Length of a Year in The Roman Calendar is 304 Days vs The 365 Days in both The Julian Calendar and Gregorian Calendar which both hath leap years with 366 Days. Not much is known about The Cult of Jupiter, only member of the cult knew much of its practices and beliefs. It is known however that members addressed Jupiter (Supreme Roman god) as Jupiter Optimus Maximus Dolichenus. Optimus Maximus is Latin for "Best and Greatest". Not much is known of the cult of Mars neither. Mars is known as the god of war so we can assume that war or battle had something to do with the practices of this cult. The Cult of Romulus was a following of The First King of Rome. This cult would later become a cult for The Sabine People known as The Cult of Quirinus. Vestal Virgins also known as just Vestals, were priestesses who worshiped Vesta, the goddess of the hearth. The hearth is the sacred fire which burned at the college of vestals which was responsible for the continuation of Rome. The Vestal Virgins were tasked with keeping the fire burning indefinitely, lest Rome fall. Numa Pompilius at first, refused to accept the throne as King of Rome, due to his belief that Rome was a nation of war and that a strong warrior leader should rule over Rome and command it's armies. He later accept the office of King by persuasion of his tutor and the father of Marcus, his son-in-law. The Second King of Roma, Numa Pompilius's reign would end in 673 B.C. where he would be succeeded by The Third King of Rome, Tullus Hostillius. If Numa Pompilius was a King of Peace and Romulus was a King of War, then Tullus Hostillius was a King of War sevenfold. Tullus Hostillius thought his predossesor was weak and therefore made The Roman Kingdom weak. Therefore the game of war was back on for Rome. Tullus Hostillius was known for The Battle of Alba Longa; a war that sought to defend the honor of Rome from The city of Alba Longa. The rules were that the last one standing would be declared victor. In the end Rome won. Though the city of Alba Longa still exists in Italy Today. Tullus Hostillius was such a War-hawk King, that he even started a war with The King of The Roman gods, Jupiter. Legends go that this is what led to the death of The Third King of Rome. Tullus Hostillius was the grandson of Hostus Hostilius, who during The Sabine Invasion of Rome, was killed in battle by The First King of Rome, Romulus Rex. Tullus Hostillius would end his reign when he died in 642 B.C. His succcesor would come to the throne in 642 B.C., The Fourth King of Rome, Ancus Marcius. Ancus Marcius was declared Interrex ,between kings, of Rome by The Roman Senate and would later be Crowned Fourth King of Rome in a session by The Assembly of The People. Ancus Marcius, later his predecessor and Romulus, would also be a King of War. His mother, Pompilia, was the daughter of The Second King of Rome, Numa Pompilius. The First Act as King of Rome for Ancus Marcius was the reenstate the religious edicts set forth byt The Second King of Rome, Numa Pompilius, which were removed by The Third King of Rome, Tullus Hostillius. Later on, The Native Latins would start a War with Rome to regain the lost territory The Roman Kingdom occupied in Latina. At the time, The Latin occupied The Aventine Hill which was one of the seven hills that form the territory of The City of Rome. Thinking that invasion would cause Ancus Marcius to fold and ask for diplomatic peace attacked The Roman Kingdom. This was a huge mistake, for Ancus Marcius was in fact, a King of War. This caused Ancus Marcius to declared War with The Latins, after the Latins refused to pay restitution money. Ancus Marcius would march into The Latinium City of Politorium, by storm and the Latins were removed from The City. Politorium would later be destroyed by The Romans. After the sacking and demolision of Politorium, The Roman would do the same to The Latinium Cities of Ficana and Tellenae. After that, the battle was set for The Latinium Town of Medullia. After many tries at the well fortified town, The Romans would eventually sack Medullia and bring home loot after the battle. After that Rome would take over the Latin town of Janiculum and make it a part of Rome and take in Latins as Roman Citizens. The great expansion of The Roman Kingdom would begin and the influence of The Tiber River was to The Romans. The Absolute Victory of The Trojans over The Latins was clear. At the age of 60, The Fourth King of Rome, Ancus Marcius would die of natural causes in 617 B.C. He left behind and bigger and more powerful Roman Kingdom. His successor would be The Fifth King of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, also known as Tarquin The Elder. His reign would mark the beginning of The Etruscan Dynasty in The Roman Kingdom. The Estrucans are from The Central Italian Region of Etruria which is modern day Tuscany, Umbrea and Lazio. Lucius waged a new war with The Latins, where he expanded Roman terriority even further. He first took the Latinium town of Apiolae, after Lucius conquered many other towns in Latinium bringing them into The Roman Kingdom. The Latins would eventually ask for support from The Sabines and The Estrucans but eventualy Rome would cease Total Victory over Latinium. After The Victory against Latinium, Lucius waged war against The Sabines. Even though The Sabines were great in battle, Lucius was able to stealthily attack the Sabine base at nightfall. He attacked using boats with flames pushed down the river catching The Sabine base on fire. While The Sabine military was busy trying to put out the fire to their camp, The Romans moved in and destroyed the Sabine Camp completely. Later in 585 B.C., The Sabines would lead an assault against The Roman Army but Lucius's troops would stand ground and declare victory on September 13th, 585 B.C. With this, The Latinium towns of Cameria, Old Ficulea, Meduilia, Nomentum, Corniculum and Ameriola would be conquered and brought into The Roman Kingdom. Later on Lucius would seek peace with The Estrucans, however they would declare war on Rome. The Estrucans would first capture The Roman Colony named Fidenae; which would become the central point in The Estrucan War. In the end however, Rome would have victory over the Estrucans and Rome would become greater due to the loot from The Estrucans. In 579 B.C. an assassination of Lucius was carried out by those who believed the successor of The throne should of been the son of The Fourth King of Rome, Ancus Marius. In a set-up riot, Lucius was assassinated with an ax to the skull. The Queen however, lied and said The Lucius was not dead, but merely wounded. She took advantage of the confusion and placed Servius Tullius as regent. Once it was established that Lucius was killed, Servius Tullius would become The Sixth King of Rome in 578 B.C. Servius Tullius Rex was most known for his reforms to The Roman Kingdom which expanded Roman Citizenship to lower class Romans and non-Romans. This made Servius Tullius a Popular King. He would reign for 44 years until he was assassinated in 535 B.C. by his daughter Tullia and his son-in-law Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. Lucius Tarquinius Superbus also known as Tarquin The Proud, would now take the throne and become The Seventh and Final King of Rome. To become King of Rome he lobbied the support of the patrician senators, especially those from families who had received their senatorial rank under Tarquin the Elder, his Grandfather and Fifth King of Rome. He gave them gifts and spread criticism of Servius Tullius Rex. Superbus Rex would eventually be dethroned by The Roman People in 509 B.C. and The Roman Republic would be created. The Etruscan oppression of The Romans was over. The Roman RepubliC Beginning in 509 BC after the fall of The Roman Kingdom by The Roman people overthrowing The Etruscan Dynasty. This happened due to The Final King of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, raping the noblewoman Lucretia who later committed suicide because of this violation of her. Lucius was then exiled by The Roman Senate led by the lobbying of Lucretia's father and Superbus's nephew to Etruria. The Roman Senate then abolished The Roman Monarchy and The Roman Kingdom and thenceforth The Roman Republic was formed. The duties of the former office of King would be for a newly established consul of two who would be annually elected The Senate. The First Two Consuls in The Roman Republic were Lucius Junius Brutus and Lucius Collatinus. The control of The Roman Republic spanned across The whole Mediterranean World, with a cultures of The Romans, The Latins, The Estrucans, The Classical World (Greeks), The Sabine and The Octans. The name of The Roman Republic was Roma and Senatus Populusque Romanus (SPQR) which translates from Latin to The Roman Senate and People. The Capital of The Roman Republic was Rome. The Official Language of The Roman Republic was Classical Latin. Other Languages spoken in The Roman Republic included: Greek, Etruscan, Osco-Umbrian, Venetic, Ligurian, Rhaetian, Hebrew, Berber, Gaulish, Nuragic, Syriac, Sicel, Aramaic, Punic, Iberian, Coptic, Illyrian, Celtiberian, Lusitanian, Gallaecian and Aquitanian. The Official Religion of The Roman Republic was Roman Polytheism which borrowed much of its aspects from The Classical World Religion like their gods such as Zeus The King of The Classical World gods becoming Jupiter The King of The Roman gods, Aries The god of War becoming Mars The god of War and Hermes The Messenger god becoming Mercury. The type of government The Roman Republic was, was known as a Diarchic Republic meaning the leads were of two men with senators below wielding power over the nation. The Roman Republic would last until 27 B.C. and be replaced by The Roman Empire. Julius Caesar Julius Caesar, The Known Roman in The World, was known for his time as a Statesmen, A Roman General, High Priest and Roman Consul. Julius Caesar or Gaivs Ivlivs Cæsar or Gaius Julius Caesar, was born in 100 B.C. in Rome, Italy, The Roman Republic. Julius Caesar was born into a Partician Family, family being Father Gaius Julius Caesar and Aurelia. Julius Caesar was believed to be the descendant of a Famous Trojan, Julus who was the grandson of The Roman goddess Venus. This claim to ancestry would lay the ground work for him becoming a Roman god himself after his demise. In Caesar's adolescent years, he was captured by pirates and was held for ransom. Upon hearing the amount of ransom demanded, Caesar felt insulted and demanded the pirates double the amount. They accepted this demand. While captive, Caesar was said to have been a friendly guy and provided voluntary entertainment for the pirates. Before the ransom was paid, Caesar gleefully told the pirates that he would return to find them then crucify all of them. He kept good on his promise too and everyone of the pirates would be executed by way of Crucifixion. Julius Caesar would later become General of 100 Legions then Marched on Rome and become Dictator of Rome. He would eventually be assassinated by Senators of The Ideas of March, March 15th, 44 B.C. The month of July is named after Julius Caesar. more details coming soon. The Roman Empire The Roman Empire Started in 27 B.C. after The Fall of The Roman Republic by The First Emperor of Rome, better known as The Princeps, Octavius Augustus Caesar. The Capital of The Roman Empire was Rome from 27 B.C. to 286 A.D. then in Mediolanum from 286 A.D. to 402 A.D. in The Western split of The Roman Empire then in Ravenna from 402 A.D. to 476 A.D. in The Western Roman Empire, this would be the final capital of The Roman Empire till The Fall of Rome in 476 A.D. The governance of The Roman Empire was an Absolute Monarchy who was elected by Roman Senators. The Official Language of The Roman Empire was Latin with other common languages being Greek and Aramaic. The Official Language of The Roman Empire was First The Imperial Cult driven Polytheism (Classical Roman Religion) till 274 A.D., then The Solar Cult known as Sol Invictus till 380 A.D., then finally Catholicism from 380 A.D. till the fall. The Emperors of Rome The Julio-Claudian Dynasty 1. Augustus Caesar, originally known as Gaius Octavius Thurinus, was a pivotal figure in ancient Roman history, reigning as the first Roman Emperor from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD. He was born on September 23, 63 BC, into a prominent Roman family. Augustus is renowned for his role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire, marking the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Imperial era.Augustus rose to power following the assassination of his great-uncle and adoptive father, Julius Caesar, in 44 BC. He entered into a power struggle with Mark Antony, who was initially allied with him but later became a rival. The conflict culminated in the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, where Augustus emerged victorious, securing his position as the undisputed ruler of Rome. Once in power, Augustus implemented a series of reforms aimed at restoring stability and consolidating his authority. He established a new constitution, known as the "Principate," which preserved the appearance of a republic while concentrating power in his hands. He was given the title of "Princeps" (meaning "first citizen") and referred to as "Augustus," which means "revered" or "majestic," signifying his elevated status. Augustus undertook a vast program of public works and infrastructure projects, such as the construction of roads, bridges, and aqueducts, which contributed to the prosperity of the Roman Empire. He also established a professional civil service, reformed the tax system, and maintained a standing army to defend the borders. One of Augustus's most enduring legacies was the Pax Romana (Roman Peace), a period of relative peace and stability that lasted for much of his reign and facilitated cultural and economic growth throughout the empire. This period is often seen as a high point in Roman history. Augustus was a patron of the arts and literature, promoting a revival of classical Roman culture. His reign saw the flourishing of literature and poetry, with notable authors like Virgil, Horace, and Livy producing significant works during this time. Augustus Caesar died on August 19, 14 AD, at the age of 75. He was succeeded by his stepson and adopted son, Tiberius. Augustus's rule left an indelible mark on the Roman world, setting the stage for the long-lasting Roman Empire and shaping the course of Western history. His enduring influence is evident in the continued use of the title "Caesar" by subsequent Roman emperors and in the term "Augustus" itself, which has come to signify a revered and powerful ruler. 2. Tiberius Caesar, whose full name was Tiberius Julius Caesar, the second Roman emperor who ruled from 14 AD to 37 AD. He succeeded Augustus, the first Roman emperor, and played a significant role in shaping the early Roman Empire. Here is a summary of Tiberius Caesar's life and reign:Early Life: Tiberius was born on November 16, 42 BC, in Rome, to Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla. His early life was marked by political turmoil and uncertainty, as his family was involved in the complex power struggles of the late Roman Republic. Military Career: Tiberius had a successful military career, gaining experience in various Roman provinces and demonstrating his military competence. He played a crucial role in the campaigns in Germania and Pannonia. Accession to the Throne: After the death of his stepfather Augustus in 14 AD, Tiberius became the second Roman emperor. His accession marked the continuation of the Julio-Claudian dynasty's rule. Reign as Emperor: Tiberius' reign was characterized by a complex mix of achievements and controversies. He was known for his administrative reforms, maintaining the stability and prosperity of the Roman Empire, and strengthening the Roman army. However, his rule was marred by suspicions of tyranny, political intrigue, and a perceived withdrawal from the public eye, as he spent much of his later years in self-imposed exile on the island of Capri. Notable Events and Policies:

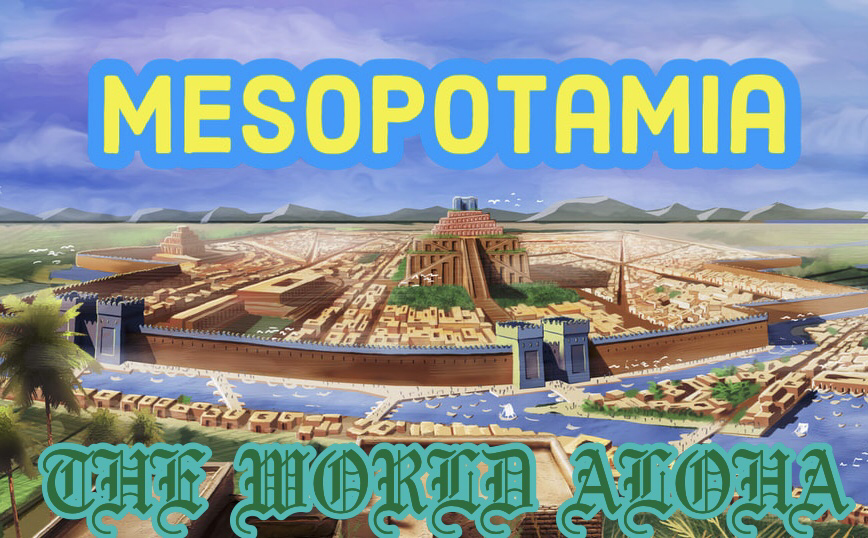

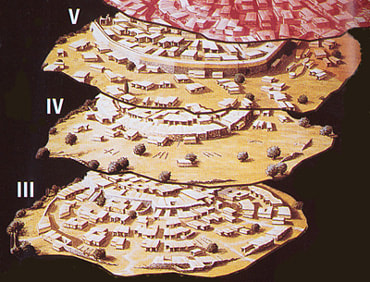

Legacy: Tiberius Caesar's reign is a subject of historical debate. Some view him as a capable administrator who maintained Roman stability, while others criticize his autocratic tendencies and the atmosphere of fear during his rule. His legacy is a complex mix of achievements and controversies that shaped the early years of the Roman Empire. Overall, Tiberius Caesar's reign remains a significant chapter in Roman history, contributing to the evolving dynamics of imperial rule in the ancient world. 3. Caligula, whose full name was Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, was the third Roman emperor who ruled from 37 AD to 41 AD. He is infamous for his tyrannical and erratic behavior during his short reign, which earned him a reputation as one of the most infamous and cruel emperors in Roman history.Caligula's early years were marked by relative stability, but after a severe illness, his behavior took a dramatic turn for the worse. He exhibited signs of madness and indulged in extravagant and often perverse behavior. He showed a particular fondness for cruelty, sadism, and sexual excesses. Some of his more notorious actions include declaring himself a god and demanding divine honors, ordering the construction of a lavish palace and floating bridge across the Bay of Naples, and engaging in incestuous relationships with his sisters. His reign was characterized by lavish spending, which strained the Roman treasury, leading to increased taxation and economic hardships for the populace. Caligula's arbitrary and violent rule led to numerous executions and purges, as well as widespread fear among the Roman elite. In 41 AD, Caligula was assassinated by a group of his own guardsmen, senators, and conspirators who sought to end his tyrannical rule. His death marked the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, which had begun with his great-uncle Augustus. Caligula's brief and tumultuous reign serves as a cautionary tale in Roman history, illustrating the dangers of absolute power and unchecked authority. 4. Claudius, was the fourth Roman Emperor from 41 to 54 AD. He is perhaps best known for his unexpected rise to power and his efforts to stabilize and reform the Roman Empire during a tumultuous period.Born on August 1, 10 BC, Claudius belonged to the Julio-Claudian dynasty, which included notable figures like Augustus, Tiberius, and Caligula. Claudius suffered from various physical ailments, which led many of his contemporaries to underestimate his abilities. Consequently, he spent much of his early life in relative obscurity. However, following the assassination of his nephew Caligula in 41 AD, Claudius was proclaimed Emperor by the Praetorian Guard. His reign marked a turning point in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Claudius implemented numerous reforms, such as expanding the Roman Empire's bureaucracy, improving infrastructure, and granting Roman citizenship to individuals in the provinces. He also undertook ambitious public works projects, including the construction of aqueducts and roads. One of Claudius's most significant achievements was the successful invasion and annexation of Britain in 43 AD, which added a valuable province to the Roman Empire. He also attempted to improve the legal system and promote the rights of the lower classes. However, Claudius's reign was marred by political intrigue and personal scandals, particularly involving his wives and family members. His fourth wife, Agrippina the Younger, played a significant role in securing the throne for her son, Nero, at the expense of Claudius's own biological son, Britannicus. Claudius's death in 54 AD remains a subject of debate and suspicion, with some suggesting he was poisoned. Nevertheless, his reign had a lasting impact on the Roman Empire. His efforts to strengthen the imperial administration and expand the empire's borders left a legacy that influenced subsequent emperors and contributed to the stability of the Roman Empire during a challenging period in its history. 5. Nero, full name Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, was the fifth Roman emperor who ruled from 54 to 68 AD. He is one of the most infamous and controversial figures in Roman history. Here is a summary of Nero's life and reign:

Year of The Four Emperors and Flavian Dynasty 6. Galba 7. Otho 8. Vitellius 9. Vespasian 10. Titus 11. Domitian  Nerva-Antonine Dynasty 12. Nerva 13. Trajan 14. Hadrian 15. Antoninus Pius 16. Lucius Verus 17. Marcus Aurelius 18. Commodus  Year of The Five Emperors and Severan Dynasty 19. Pertinax 20. Didius Julianus 21. Septimius Severus 22. Caracalla 23. Geta 24. Macrinus & Diadumenian 25. Elagabalus 26. Severus Alexander The Fall of Rome In 476 AD, The Roman Empire would officially meet its end, at least in The Western Half, at the hands of The Barbarians that it oppressed for centuries, with the sacking of Rome. Along with the sacking of Roman, political strife and unstable political structure would bring the end of The Power of The Roman Empire after 1000 years of being The World Super Power. The World's First Super Power may have fallen, but its ashes, the rise of The World we know of Today would rise and the heights of human achievement would be found. The Roman Empire may no longer exist, but its legacy is felt in Today's World and therefore, Rome's Power is eternal. The Start of CivilizationBefore Civilization began in The World, humans were Hunter Gatherers. People were nomadic due to poor environmental conditions like The Ice Age and lack of tools and knowledge to settle in one spot for an extended period of time. Wherever the food was, the humans were. After a long passing of time, humans figured out how to farm and grow food locally and this led to them settling into one particular spot are a good amount of time. This eventually gave rise to what know Today as Civilization! The First Civilization In Mesopotamia, The First recorded civilization in history was born, this city state would be known as Sumer. Sumer came about around the 4th millenium B.C. Here humans thrived on the two rivers that flowed through it known as the Tigris and Euphrates. The First City in The World would come out of Sumer, called Uruk. Legends like the Epic of Gilgamesh, The Oldest Story written known to man, were set in this Ancient city. Uruk is said to have been founded by King Enmarker in The Sumer Kingslist. The Kingslist is an Ancient text written in Sumerian that list The King of Sumer. The King's List is a long list that goes on for eons in time. I shalt go over it in order. Warning, The Kinglist is going to be split into 20 parts. The Kings List The Kingslist start with The Antediluvian Rulers. These rulers are believed to have not been truthfully historical due to the large lifespans of these rulers. This first part of The Kingslist may have been believe to be god-Kings with there Divine Powers would have been able to live very long life spans. The List Starts with Alulim who ruled for 8 Sars(28,800 Years) then Alalngar who reign for 10 Sars (36,000 Years), then Enmenluana who reign for 12 Sars(43,200 Years), then Enmengalana who ruled for 8 Sars( 28,800 Years) then Dumuzid The Shepherd who ruled for 10 Sars, then Ensipadzidana who ruled for 8 Sars, then Enmendurana ruled for 5 Sars and 5 Ners (21,000 Years) and then Ubara Tutu who reign for 5 Sars and 1 Ner( 18,600 Years). This first set of Kings ended when The Great Flood occurred. This wiped away a ton of resources and is believe by some to be The same flood that occur in The Bible in the Noah's Ark story. After the flood The Second set of Kings came to be, The First Dynasty of Kush. The Kings List Part 2 The First Dynasty of Kish begins with Jusher who ruled for 1200 Years, then Kullassina-bel who ruled for 960 years, then Nangishlishma whose reign was 670 Years, then Entarahana who reign for 420 years, then Babum who ruled for 300 years, then Puannum who reign for 840 years, then Kalibum who ruled for 960 years, then Kalumum who ruled for 840 years, then Zuqaqip who ruled for 900 years, then Atab or A-ba who ruled for 600 years, then Mashda who ruled for 840 years, then Arwium who ruled for 720 years, then Etana who reign for 1500 Years, then Balih who ruled for 400 Years, then Enmenuna who ruled for 660 years, then Melem-kish who ruled for 900 years, then Barsalnuna who ruled for 1200 Years, then Zamug who ruled for 140 years, then Tizqar who ruled for 305 years, then Ilku ruled for 900 years, then Iltasadum who ruled for 1200 years, then Enmebaragesi who ruled for 900 years; this is the first ruler to be confirmed independently, believed to have ruled around 2600 B.C.; and finally Aga of Kish who ruled for 625 years. After this dynasty the Kish were defeated and the kingship was taken to Eana. The Kings List Part 3 The third part of the Kingslist is known as The First Rulers of Uruk. The Rulers start with Meshkianggasher of Eana who reign for 324 years, then Enmerkar who ruled for 420 years, then Lugalbanda who ruled for 1200 years then Dumuzid who ruled for 100 years, then Gilgamesh who is from the oldest story in The World; The Epic of Gilgamesh; ruled 120 years, then Ur Nungal ruled for 30 years, then Udul-kalama who ruled for 15 years, then La-ba'shum who ruled for 9 years, then Ennuntarahana who ruled for 8 years then Meshhe The Smith ruled for 36 years, then Melemana who ruled for 6 years and finally Lugalkitun who ruled for 36 years. This era in The Kingslist ended when The Unug was defeated and the Kingship was taken to Ur. The Kinglist part 4 The fourth part of The Kingslist is the First Dynasty of Ur which starts with Mesh Anepada who reign for 80 years, then Meshkiang Nuna who ruled for 36 years, then Elulu who ruled for 25 years and finally Balulu who reign for 36 years. When The Urim were defeated, the kingship was brought to Awan The Kingslist Part 5 The Fifth part of The Kingslist is not very long. It is known as The Dynasty of Awan. These were ruled by The Three Kings of Awan who ruled for 356 Years. After this reign The Awan were defeated and the kingship was returned to its original spot of Kish. The Kingslist part 6 The Sixth part of The Kingslist is called The Second Dynasty of Kish,. This part begins with Susuda The Fuller who ruled for 201 Years, then Dadasig who ruled for 81 Years, then Mamagal The Boatman who reign for 360 years, then Kalbum who ruled for 195 years, then Tuge who ruled for 360 Years, then Mennuna who ruled for 180 Years, then Enbi Ishtar who ruled for 290 years and then Lugalngu who ruled for 360 years. The dynasty of Kish ended when it was defeated and the kingship was brought to Hamazi. This Dynasty is not in The Kingslist but known from other inscriptions outside the Kingslist. The Ruler Hadanish ruled for 360 Years and Hamazi was defeated and brought back to Uruk The Kingslist Part 7 The Seventh part of The Kingslist is The Second Dynasty of Uruk. The list begins with Enshagkushana who ruled for 60 years, then Lugal-kinishe-dudu or Lugal-ure who ruled for 120 years and Argandea who ruled for 7 years. Uruk would be defeated by Ur and The Kingship would return to Ur. The Kingslist part 8 The Eight Part of The Kingslist is The Second Dynasty of Ur. The Second Dynasty of Ur consist of Nanni who ruled for 120 Years and Meshkiang Nanna II who ruled for 48 Years. Ur was defeated and The Kingdom was brought to Adab. The Kingslist part 9The Dynasty of Adab had only one known ruler on The Kinglist. The ruler was Lugal Anemundu who ruled for 90 years. The Kingdom was brought to Mari after the defeat of Adab. The Kingslist part 10The tenth part of The Kingslist was known as The Dynasty of Mari. It starts with Anbu who ruled for 30 years, then Anba who ruled for 17 years, then Bazi The Leatherworker who ruled for 30 years, then Zizi of Mari The Fuller who ruled for 20 years, then Limer The 'gudug' priest who ruled for 30 years and Sharrumiter who ruled for 9 years. The Mari were defeated and The Kingdom was returned to Kish for the third time The Kingslist Part 11The Third Dynasty of Kish was ruled by Kug Bau The Women Tavern-keeper who made firm the foundations of Kish for 100 years. Kish was defeated and brought to Akshak. The Kingslist Part 12The Dynasty of Akshak was ruled first by Unzi who ruled for 30 years, then Undalulu who ruled for 6 years, then Urur who also ruled for 6 years, then Puzur Nirah who ruled for 20 years, then Ishu-II who ruled for 24 years and Shu Suen of Akshak who reign for 7 years. Akshak was defeated brought to Kish for a fourth time. The Kingslist part 13The Fourth Dynasty of Kish begins with Puzur Suen The son of Kug-Bau who reign for 25 years, then Ur Zababa for 400 or 6 years (questionable translation)' Sargon of Akkad was his cupbearer, then Zimudar who ruled for 30 years, then Usiwatar who ruled for 7 years, then Eshtarmuti who ruled for 11 years, then Ishme Shamash who ruled for 11 years, then Shuilishu who may have ruled for 15 years, and Nanniya The Jeweller who ruled for 7 years. Kish was defeated for a fourth time and The Kingdom was brought back to Uruk for a third time. The Kingslist part 14The third dynasty of Uruk was ruled by Galzagesi who ruled for 25 years. Uruk was defeated by Akkad kickstarting the Akkadian Empire. The Kingslist part 15 The Dynasty of Akkad also known as The Akkadian Empire or The First Empire was ruled by Sargon of Akkad, also known as The First Emperor who ruled for 40 years. After that The dynasty was ruled by Rimush of Akkad for 9 years, then Manishtushu for 15 years, then Naram Sin of Akkad for 56 years, then Sharkalisharri for 25 years, then it was split between Irgigi, Imi, Nanum and Ilulu for 4 years, then Dudu of Akkad for 21 years and Shu Durul for 15 years. Uruk defeated The Akkadian Empire and took The Kingdom to Uruk for The Fourth time. The Kingslist part 16The Fourth Dynasty of Uruk was ruled by Urningin for 7 years, then Urgigir for 6 years, then Kuda for 6 years, then Puzurili for 5 years and finally Ur Utu or Lugalmelem for 25 years. Uruk was defeated for a fourth time and taken to Gutium. The Kingslist Part 17The Guitian Rule or also known as The Gutian Dynasty was ruled first by Inkishush or Inkicuc for 6 years, then Sarlagab or Zarlagab for 6 years, then Shulme or Yarlagash for 6 years, then Elulmesh or Silulumesh who reign for 6 years then Inimabakesh or Duga who ruled for 5 years, then Igeshaush or Ilu An who ruled for 6 years, then Yarlagab who ruled for 3 years, then Ibate of Gutium who ruled for 3 years, then Yarla who ruled for 3 years, then Kurum who ruled for 1 year, then Apilkin who ruled for 3 years, then Laerabum who ruled for 2 years, then Irarum who ruled for 2 years, then Ibranum who ruled for 1 years, then Hablum who ruled for 2 years, then Puzur Suen who ruled for 7 Years, then Yarlaganda who reign for 7 years, then an unknown King ruled for 7 years and finally Tirigan ruled for 40 days. The Army of Gutium was defeated by Uruk and The Kingdom was returned to Uruk for a Fifth time. The Kingslist Part 18The Fifth and final dynasty of Uruk was ruled by Utu-hengal who might have ruled 427 years or 26 years or 7 years. The writing is not precisely clear on the manner. Uruk was defeated by Ur and The Kingship was returned to Ur for the Third time The Kingslist Part 19The Third dynasty of Ur was ruled by Ur Namma or Ur Nammu for 18 years, then Shulgi for 46 years, then Amar Suena for 9 years, then Shu Suen for 9 years and Ibbi Suen for 24 years. Ur was defeated by Isin and consequently brought to Isin. The Kingslist part 20The Final part of The Kingslist is The Dynasty of Isin. The rulers of this dynasty are Ishbi Erra who ruled for 33 years, then Shu-Illshu who ruled for 20 years, then Iddin Dagan who ruled for 20 years, then Ishme Dagan who ruled for 20 years, then Lipit Esthar who ruled for 11 years, then Ur Ninurta who ruled for 28 years, then Bur Suen who ruled for 21 years, then Lipit Enlil who ruled for 5 years, then Erra imitti who ruled for 8 years, then Enlil bani who ruled for 24 years, then Zambiya who ruled for 3 years, then Iter-pish who ruled for 4 years, then Urdukuga who ruled for 4 years, then Suenmagir who ruled for 11 years, the last but not least, Damiq-ilishu who may have ruled and may have ruled for 23 years, it's not clear on the text. With that, this was the complete Kingslist known to man. The First Empire Let's go back to Sargon of Akkad and The Akkadian Empire. The Akkadian Empire was The First Empire in THe World and Sargon of Akkad was The First Emperor in The World. Sargon of Akkad was also known as Sargon The Great. The Center of The Akkadian Empire was of course Akkad. The First Empire of The World influence Power across Ancient World Mesopotamia, The Levant & Anatolia. This empire spaning in The Bronze Age from 2334 B.C. to 2154 B.C. The Akkadian Government, which was a Monarchy, established The Classical Standard. All future Mesopotamian States would try to match this Classical Standard. Traditionally, The Ensi, who was The Priest of The Land, had Supreme Power with The King, The Lugal, underneath The Ensi. This changed under Sargon of Akkad who believe he ruled The Totality of Lands Under The Heavens. Sargon believed he ruled The World. Little did he how big The World actually is. His empire however was not small by any means extending to a surface greater than alot of European and African Nations in Today's World. The Akkadian Empire is believed to have ended due to a curse. The Sumerians believe a curse set by Naram-Sin, when he conquered The City of Nippur and demolish The Temple. Babylon Babylon, Capital City of Babylonia; is a staple to the timeline of Ancient Mesopotamia. Babylonia reigned as a Kingdom from 18th Century B.C. to 6th Century B.C. The First Emperor of Babylonia was King Hammurabi. This King's notary come from the fact that he established The first written code of Laws. This system of laws was known as Hammurabi's code or The Code of Hammurabi. The Laws gave clear guidelines on what was legal and illegal and what the punishments were for violating the law. The main rule of thumb was "An Eye for an Eye & a Tooth for a Tooth." This was known as The Law of Retaliation. A few of the crimes and punishments were: Theft which would result in execution, Slander which would result in the cutting of skin or hair, Fraud which would result in the criminal paying the victim tenfold the amount of the fraud & perjury would result in Execution. The End of MesopotamiaMesopotamia never really ended in a since. Mesopotamia has many period throughout The Ages. The Stone Age saw Pre Pottery Neolithic A from 10,000 to 8700 B.C., Pre Pottery Neolithic B from 8700 B.C. to 6800 B.C., Jarma from 7500 B.C. to 5000 B.C., Hassuna from around 6000 B.C. to unknown, Sammra from 5700 B.C. to 4900 B.C., Halaf Culture from 6000 B.C. to 5300 B.C., Ubaid period from 5900 B.C. to 4400 B.C., Uruk period from 4400 to 3100 B.C. & Jemdet Nasr period from 3100 B.C. to 2900 B.C. The Early Bronze Age had Early Dynastic period from 2900 B.C. to 2350 B.C., Akkadian Empire from 2350 B.C. to 2100 B.C., Third Dynasty of Ur from 2112 to 2004 B.C. & Early Assyrian Kingdom for 24th century B.C. to the 18th century B.C. The Middle Bronze Age saw Early Babylonia from the 19th century B.C. to the 18th century B.C with this age ending with the Minoan Eruption in 1620 B.C. This eruption is believed to be caused by The Hebrew Exodus from Egypt ' The splitting of the red sea' which would have caused a tsunami to devastate the Minoan civilization. Call divine intervention or just pure luck, but if the story is factual, then this event in history affected more than just The Egyptians. The Late Bronze Age saw The Old Assyrian PEriod from the 16th to 11th century B.C., The Middle Assyrian Period from 1365 to 1076 B.C., The Kassities of Babylon from 1595 B.C. to 1155 B.C. & The Late Bronze Age Collapse from The 12th century B.C. to The 11th Century B.C. The collapse was said to be brought upon by The Sea Peoples who caused the collapse. The Bronze Age collapse affected Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and more civilizations at the times. The Sea People were said to be a naval brigade of sea raiders who sacked and destroyed coastal towns across the mediterranean. One theory on who The Sea Peoples were, were The fleeing Trojans who escaped The destruction of Troy during The Trojan War. As The Trojans made their way to Latania, later Rome, they left a path of destruction wherever they lay siege. More contemporary theories however blame change in climate and fertility of the soil which cause The Bronze Age collapse. The Iron Age saw The Syro-Hittite States from The 11th century B.C. to The 7th century B.C., The Neo-Assyrian Empire from The 10th Century B.C. to The 7th Century B.C. & The Neo-Babylonian Empire from The 7th century B.C. to The 6th century B.C. The Classical World or Classical antiquity period saw Persian Babylonia & Achaemenid Assyria from the 6th century B.C. to The 4th Century B.C., Seleucid Mesopotamia for The 4th century B.C. to The 3rd century B.C., Parthian Babylonia from The 3rd century B.C. to The 3rd century A.D., Osroene from The 2nd century B.C. to The 3rd century A.D., Adiabene from The 1st Century A.D. to The 2nd Century A.D., Hatra from The 1st Century A.D. to The 2nd Century A.D. & The Roman Mesopotamia from The 2nd century A.D. to The 7th century A.D. The Late Antiquity era, the final era, had The Palmyrene Empire for The 3rd Century A.D., The Asoristan from The 3rd century A.D. to The 7th century A.D., Euphartensis from The mid 4th century A.D. to the 7th century A.D. & last but not least The Muslim conquest in The mid-7th Century A.D. The Muslim conquest is seen as the end of Mesopotamia due to the fact of cultural, religious and name change of the area of land. The Traditional Mesopotamian gods were replaced by the god of Islam, Allah. Today's World's Mesopotamia is now called Iraq. Mesopotamia is the cradle of civilization and have inherited maybe aspect of Today's society from Mesopotamia. Western Civilization is even said to have its origins in Mesopotamia. Three of The World's Major Religions, The Abrahamic Religions, Judaism, Christianity & Islam have their origins in this plot of land. The concept of written laws and punitive measures come from Mesopotamia. Mesopotamia is the bedrock of many of the essential aspects of society of today. Without it, would civilization even have stuck around in the course of human history? We have a lot to be thankful for from The World's First Civilization, Mesopotamia!